Economic and Financial Market Update: Full employment the eternal goal

Summary:

- The Australian jobs market remains in a strong state;

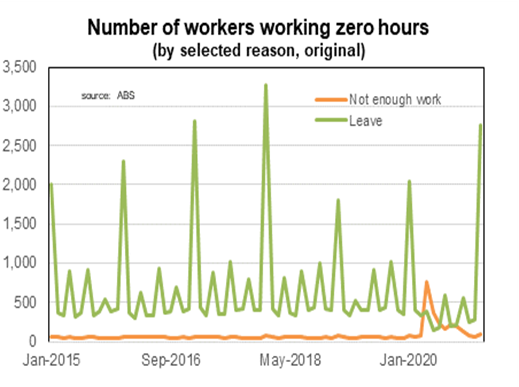

- The January Omicron-driven weakness was concentrated in hours worked;

- All regions are benefitting from the strong labour market;

- Low immigration growth is a factor behind the very low unemployment rate. But so is the extremely strong demand for workers.

The January labour market numbers were pretty much in line with expectations. Much of the weakness in the labour market reflected a big drop in the number of hours worked. The main reason for the large drop in hours worked was a big rise in the number of people taking leave. The big fall in hours worked means there is a high chance that the economy grew only modestly in Q1. But barring the arrival of another COVID wave over the next 8-10 weeks economic growth is on track to be very strong in the June quarter.

The RBA has been emphasising the importance of a very low unemployment rate for wider economic and social reasons. As at the end of last year the strong jobs market had resulted in some decline in long-term unemployment (although it remained high by historical standards). But with forecasts that the unemployment rate is likely to be in the ‘3’s’ by end-year 2022 and vacancies at a very high level further declines in long-term unemployment are virtually certain.

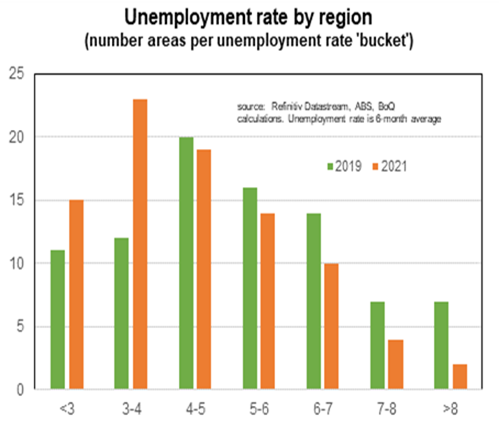

A very low unemployment rate is benefitting all regions across Australia. Over the past two years there has been an increase in the number of regions with very low unemployment rate and a reduction in the number of regions with a high unemployment rate.

There is an expectation that the strong jobs market will lead to rising wages growth. The RBA thinks that wages growth will be 3% by the end of 2023. Most financial market economists expect wages growth to hit that mark later this year. One argument about why the pickup of wages growth will be slower is how wages are set in Australia. The thinking is that multi-year enterprise bargaining agreements and current state government wage policies will make it difficult for aggregate wages growth to rise quickly. This needs to be offset by the rising anecdotal evidence from firms about rising labour costs.

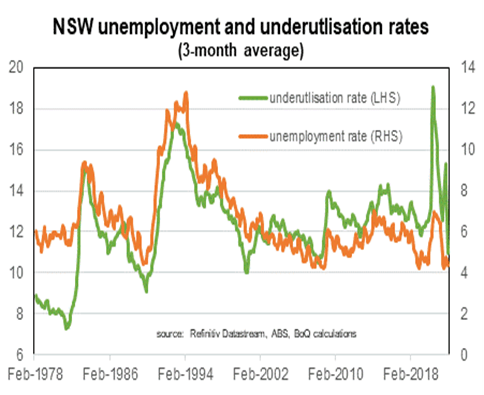

The RBA noted that the unemployment rate reached 4% in NSW (and Victoria) pre-COVID without there being any significant rise in wages growth. But unlike last time the underutilisation rate has declined sharply in NSW (as it has elsewhere) and is now at its lowest level since the GFC.

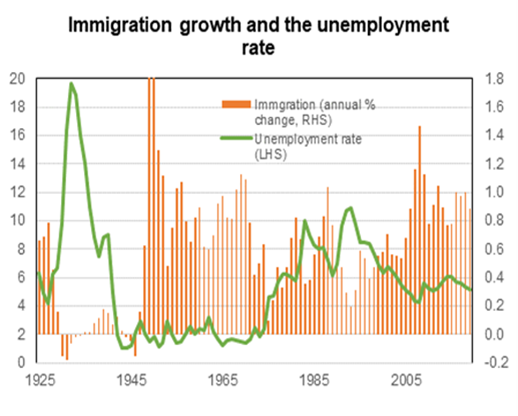

It has been suggested that the sharp decline in the unemployment rate has reflected the lack of immigration. The history of movements in the unemployment rate and immigration if anything indicates the reverse relationship. Of course this time the driver of immigration flows was not economic (the unemployment rate) but government health policy. In that respect the current situation is closer to what happened during World War II, a time when both the unemployment rate and immigration growth was low.

The demand for workers currently is back near mining boom strength at a time of a slow increase in the supply of workers. The fall in the unemployment rate this time might have been slower if immigration was at pre-pandemic levels. But such is the current demand for workers a fall in the unemployment rate to a very low level would most likely still have taken place even if immigration was higher.

A strong labour market is unambiguously a good thing. It means that the economy is fulfilling its potential. Ensuring that most people who want a job can get one reduces income inequality in society. The key question though is how many jobs can be created without leading to other economic problems (particularly inflation). That is currently what we are finding out. The answer to that question is also the answer to when interest rates will begin to rise (and partly, how high interest rates will rise in this cycle).

To read my full update, click here.

We live in interesting times.

Regards,

Peter Munckton - Chief Economist